Design Elements to Consider when Designing a Garden

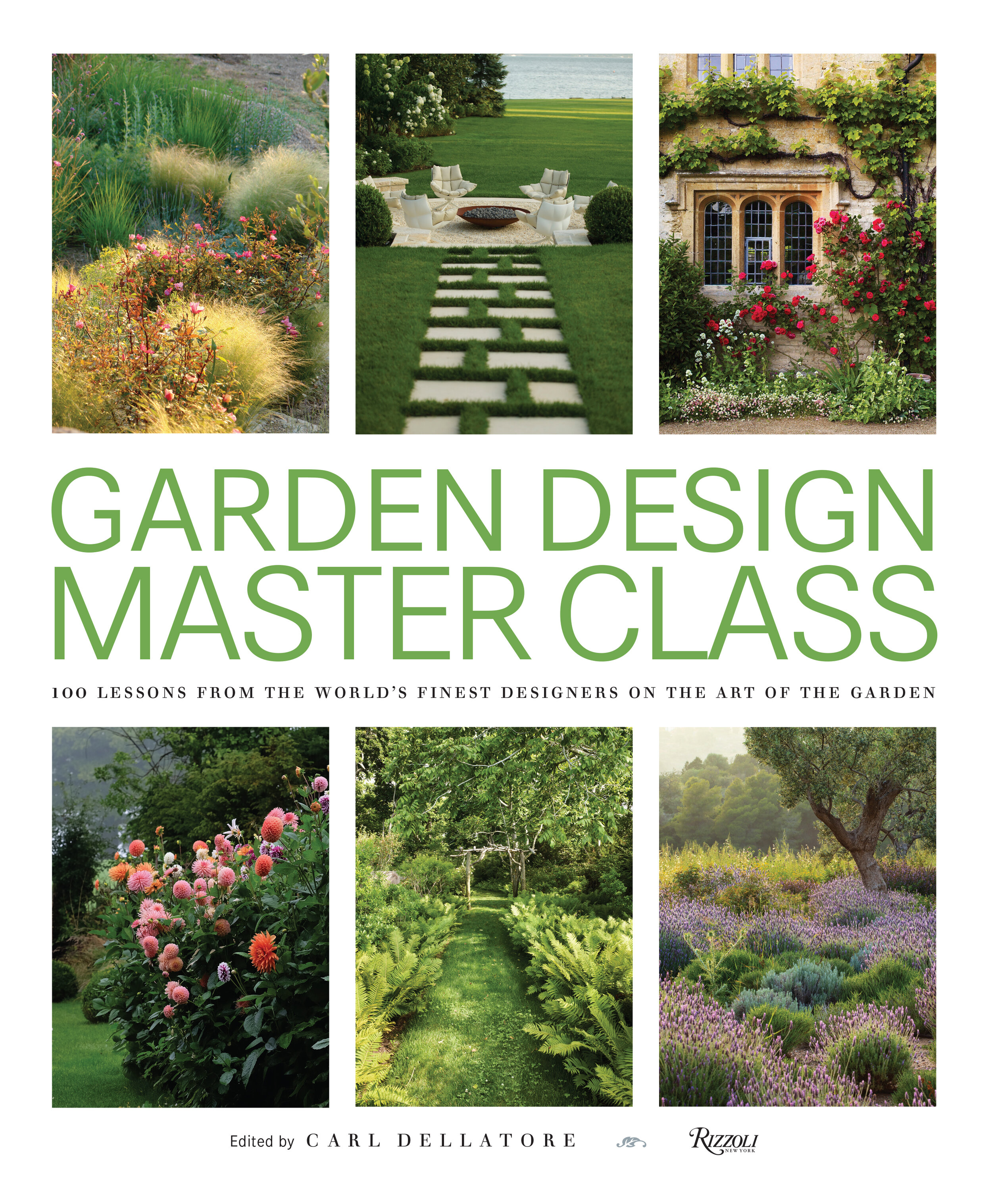

Creating an oasis that you can enjoy in the comforts of your backyard, no matter how big or small, seems even more important now than ever. Whether it’s a plot dedicated to vegetables or cutting flowers, cultivating your own garden is one of the most rewarding things during the warmer months. For those looking to create their own green space and looking to get inspired, we recommend picking up the new book Garden Design Master Class: 100 Lessons From the World’s Finest Designers On The Art Of The Garden by Carl Dellatore (Rizzoli), hitting bookstores April 14th. As the title suggests, Dellatore taps into the expert advice from garden designers around the globe on the elements that they believe can create an impactful landscape.

Take INspiration from an English Garden

JINNY BLOOM (above)

We know our own societies intimately, and activities that might appear outlandish to a foreign visitor are so culturally familiar to usthat they are never questioned. This is certainlythe case with the English and their passionfor gardens. Along with their enthusiasm for dogs and the weather, the British speak gardening fluently. Quite literally, every British householder with access to a scrap of earth will garden in some way, shape, or form.Splendid gardens are not solely the province of the rich and mighty. For a country with such a pronounced class system, it is interesting to note that gardening in England unifies everyone with unparalleled generosity.Although the great gardens of the country do, invariably, have great houses attached, humbler gardens are also available to the admiring eyes of passersby. English gardens are created to be shared. The cottage garden of English villages has become part of our folklore, and they are often seen from the street as they sit in front of homes surrounded by low walls. Charmingly disheveled and brimming with a nonchalant assortment of summer flowers tumbling this way and that, they are as well known worldwide as Her Majesty the Queen. Many biscuit tins and tea towels have been decorated in honor of thecottage garden. Even in intensely urbanized areas, gardens abound and become more inventive and outlandish as constrained space and apartment-block altitude dictate.The enormous breadth of gardening creativity in our islands has a great deal to do with that other English obsession: the weather. A temperate climate allows theBritish Isles to grow the most astonishing spectrum of plants. Plant hunting has been here for centuries, and specialist nurseries crowd the land as a result.

So what is the essence of an English garden? In my opinion, it has to be a subtle balance of structure and disorder. A really good English garden can be viewed with pleasure at any time of year, even in winter, when the bones are laid bare. Fascinating networks of paths lead to secret garden rooms.Arches in hedges open onto magnificently framed landscape vistas and then turn back toward the “wilderness” of naturalistic gardening. The English garden is salted andpeppered with charming details like sculptures,fountains, meads of long grass, lakes, and thatprince of the English garden, the ha-ha, orsunken fence, the purpose of which was toprovide the illusion of unbroken lawn from thehouse, while still containing grazing animals.I am a true disciple of English gardening.My gardens look very structured on plan,with rooms and paths, and yet, in person,they are overwhelmingly soft, flowery, andnaturalistic. Our structure is there to supportthe real divas: the plants.

The key to creating this look is tounderstand green structure and the art oflayering plantings. Of vital importance is astrong network of architectural plants. Usingpleached trees—trees trained as stilted hedges—is a good place to start. A garden room can becreated entirely with a perimeter of pleachedhornbeam (Carpinus betulus) standing fourteenfeet high and wrapped at the base with asolid yew hedge (Taxus baccata). A structuralbackdrop is now clearly laid out usingevergreen and deciduous trees to great effect.Shrubs cut to a straight edge need softening,so I would suggest planting a naturally shapedtree behind the pleached line. This givesdepth to the view and also textural changes.England is the home of the generousherbaceous border. These borders need therigidity of the green structure to give thembackbone and sustain the tumult of plantingover the summer season. Often a large border, say twelve feet deep by one hundred feet.

The Italian Garden

Luciano Giubbilei

I grew up in Siena, down one of the narrow, shaded streets radiating from the Piazza del Campo. There was a small park near my grandmother’s home, where I played with my school friends: a simple space of chestnut and pine trees, brick walls, travertine benches, and a vast gravel surface on which to kick a ball. The park had no particular distinguishing features, apart from the scent of privet flowers, the faintest hint of which still transports me instantly back to my childhood. Although I spent most of my time outside, I do not recall any gardens.Everything changed for me at Villa Gamberaia, outside Florence, where I worked briefly as a teenager. In this perfect convergence of Renaissance, Baroque, and twentieth-century sensibilities, I found myself steeped in a seamless green universe of harmony, proportion, balance, order, rhythm, repetition, scale, explicit formality, and implicit sensuality.

The characteristics we associate with the structure and atmosphere of Italian gardens originate in Renaissance preoccupations with science, mathematics, art, and humanity.These are gardens defined by their bold geometry and extended lines of perspective, articulated in stone, verdure, and water, but this is also territory designed for human movement—of the body and the eye. Thesense of place is powerful, but equally powerful is the experience of being locatedin space as one walks. To engage staticallywith a part in isolation risks losing the entiremeaning of the garden. As Edith Wharton puts it, “. . . the blending of different elements,the subtle transition from the fixed and formallines of art to the shifting and irregular lines of nature [. . .] of straight lines of masonry and rippled lines of foliage. . . .”

Dialogue is intrinsic to the encounter.The garden must be understood in relationto the house, and both co-opt the enclosing landscape as part of the same layeredomposition. Each part exists in relation to another, just as Renaissance painters art fully assembled people, action, and architecture against a receding horizon of valleys and hills, the difference being that, in the case of the villa and its garden, the frame of view is constantly and dynamically shifting, the canvases potentially infinite.

There is an idea that, historically, there has only ever been a very subordinate place for flowers in Italian garden design. The rigorously restricted palette that developed in response to this belief, however, has resulted in some of the most exquisitely refined, spatially charged gardens to be found anywhere: places of graphic clarity and tonal subtlety, where the visual field is filled by a thousand shades of green and the mellow hues of weathered stone. Two and a half decades after I left Siena for London, I have been creating my firstItalian garden, in the Val d’Orcia region ofTuscany. Many influences have helped shapemy design thinking over the interveningperiod, but there is resonance in the fact that the essence of the garden became clear to me in the observation of the interaction oneevening of the setting sun, an old oak tree, andan expanse of wall. In this moment, I saw a thread of thought leading directly back to the trees, the clipped hedges, the stone, and the play of light and shadow in the park where I played football as a boy.

Creating Balance

John howard

As humans, one of our basic desires is to find balance. We yearn for balance between our work life, personal life, physical life, and spiritual life. Living in an environment of beautyis one important way to inspire a sense ofharmony and well-being. Gardens connect usto the rhythms of nature and put us on the pathtoward inner peace.From an early age, I was profoundlyinspired by art, nature, and athematics,especially geometry. Studying landscape architecture seemed like a natural thing to do, but it wasn’t until I started traveling abroad on a regular basis that I discovered great gardens and, as a result, found my true calling. Travelsin France and Italy first opened my eyes togardens of enduring beauty. Observing the structure of stone, brick, and stucco in buildings, walls, terraces, and walks woven seamlessly with water, lawns, borders, hedges, groves, and allées awakened me to the power of the manmade landscape. In these gardens, I felt morealive and more at peace than ever before.

The genius of European gardens hasinfluenced my work to this day. The classicgardens across Europe have lasted and beennurtured for a reason—they induce tremendousemotions. That is one of the principal reasons these great gardens have endured. An extraordinary garden is about more than just being in nature with earth, plants, and sky.Classic gardens have an organized structure and are put together in a deliberate, harmonious way using the architecture of hard materials combined with nature’s living green palette.They are intentional, and they are inspiring.In garden design, balance is a condition in which different elements are either in equal parts or correct proportions to one another. The use of axis and symmetry are powerful tools in the geometry of Italian, French, and English gardens; I use these conventions in my own work to great effect. A garden with a central lawn or path with flanking borders, a garden divided into quadrants, or a boxwood parterre please the senses with their geometry, order, and finesse. But geometry is not enough to make a garden great if the contrast in details is not present. Having the right mix of contrasting elements creates equilibrium; one aspect cannot be fully understood without the other.

Where there are clipped hedges or hardlines, there should also be something softfor contrast, such as water or a voluptuous planting. Large spaces are more meaningfulnext to smaller spaces. Open lawns are morebeautiful juxtaposed against shrub bordersor woodland. Flat spaces are more impactful when adjacent to a hillside or a level change.Contrast creates a dynamic synergy that inspires a feeling of life. We can always learn from history, andthe enduring gardens from times past canteach us about geometries and patterns thatresound with the human experience. Beautycan be felt, and how to create beauty can bediscovered from these places.One of the most satisfying rewards ofdesigning gardens is recognizing the impact onthe lives of my clients. Whether designing an outdoor urban space or a country garden in the mountains, my creations ultimately influence the emotional well-being of their owners. When the outcome of my creativity results ina beautiful and peaceful place that helps themachieve personal balance and happiness, Iconsider my efforts a success. My wish is thatthey will, in turn, positively impact the lives ofcountless others from their place of serenity.

Embracing Informal Elements

Dan Pearson

The principle of informality was instilled in me at an early age and remains the defining element in my design work. I was brought upon an acre of land that had long overwhelmedthe previous owner. When my family moved there in the mid-1970s, the surrounding woodland had reclaimed the garden and made a start on the house, with laurel pressed heavy against the windows and Akebia quinata—chocolate vine—finding its way under the skirting boards and wrapping its tendrils around the furniture. As we cleared five decadesof woodland that had colonized the formalborders, a pond, the lawns, and an orchard, wediscovered a previous order. From thisI understood immediately that nature alwayshas the upper hand. As a young gardener,I decided very quickly that it was better towork with nature and not against it.

Horticulture and the art of growing plants soon became my vocation. By my late teens, I was going out into the world to look at different ecologies that either had their own order or had developed through the influence of man. Itraveled to the exquisite mountain meadows ofthe Picos de Europa in Spain, which at thatpoint were still maintained according to medievalfarming principles. While studying at the Jerusalem Botanical Gardens, I saw the flora of the Negev Desert blooming; I then went onto the wilder Himalayas and further, in pursuit of the few remaining primitive landscapes where the hand of man is barely visible.With my horticultural training, I learned the formalities of gardening and the process of ordering nature. However, the naturalworld has always been my first port of call forinspiration. Through observing plants in thewild, I have learned to ground my gardensand key them into their setting with plants thatare chosen for their appropriateness to theto encourage this as much as possible. Thegardens I design are intended to be places ofsanctuary for their owners as much as theyare for the many plant inhabitants that coexistwhen a balance is struck.

Where my gardens may appear to be loosely assembled, with a simple hard landscape providing clean bones for soft, layered planting, they do depend upon a degree of structure to maintain coherence: a viewpoint, a calm place where a clean lawn might allow the play of shadows, a path that clearly beckons or leads somewhere, or the reflective quality of water to bring the sky to earth. The key to coherence is balancingthese elements so that they help to pacethe experience as one moves through thegarden—light against dark, weight against weightlessness, the ephemeral against thegravity of something that appears unchanging.The gardens of Japan are a good exampleof this. The apparent asymmetry, where elements appear to be informally arranged,is, in fact, the result of extremely rigorousformal thinking, where each and everyelement is calibrated according to a set ofrules. There is the positioning of the visualweight or physical mass of an eye-catcher,be it something strongly material such as aboulder or clipped evergreen form, or themore ephemeral brilliance of an autumnalJapanese maple in full leaf. And then there is the discipline of close observation, the achievement of balance, and the honing back only to what is absolutely necessary.Symmetrical balance is obvious and easily read. It immediately places one ina rational and predictable world whereboundaries are known and routes are evident.

Asymmetry is something to be discovered,intuited, and felt. It’s a place where boundariesare mbiguous, pathways are meandering, andthe journey is yours to invent. A structured garden reveals the designer’s hand more readily and leaves less room for interpretation, where as a less structured space is about creating a feeling, emotion, or mood. The creation of the appropriate emotional note inmy gardens is fundamental, as they areplaces designed to enhance, intensify, or transcend their surroundings.

Add Some Structure

Charlie Baker

When you hear the word garden, your first thought is most likely of plants—colorful blooms and textural leaves. But while plants may play a starring role, without structure a garden is no different than a nursery. Structure is where my personal design process begins and ends. Structures serve many purposes in a garden, but they begin as the backbone of the design. This foundation provides direction for the visitor, serving as a guide to help him or her navigate the outdoor space. Whether it is a gate that encourages entry, an arbor that provides transition from one outdoor living area to the next, a patio that invites you to stay for an outdoor meal, or a pergola that provides shelter from the sun, structures domesticate the landscape, transforming it from an abstract space into a functional one.

Besides creating order, structures are integral to the garden’s aesthetic. Theyshould be designed as an extension of the style and architecture of the house as well as an accent to the existing landscape beyond the garden. Designing them as part of their natural surroundings is particularly important in the country garden. There, I strive to create pieces that look as if they could have grown from the ground instead of being the work of my hands. I naturally gravitate toward more organic materials that appear borrowed from the wilderness. This way, there is less separating the structures’ materials from the complementing plants. Climbing vines seem to coexist or intertwine with the pergola or arbor that supports them. Pathways and patios seem carved out of the landscape, rather than placed.

This is not to say that garden formations should be camouflaged in their setting; they should be integrated within. They can serve as focal points and eye-catching highlights of a garden. When we experience the untamed, un-landscaped outdoors, we are drawn to naturally occurring formations, craving an interaction with them. A fallen tree trunk over a stream wants to be crossed; a cave or hollow tree trunk wants to be explored; and a rock outcropping wants to be climbed.

I love the idea of borrowing scenery. Many of the things I build for gardens follow this process. A pergola built for a waterfront property on Shelter Island, New York, for example, was composed predominantly of driftwood, a material cultivated by the seascape. The driftwood gate and tunnel formation of the pergola invited visitors down to the water. A gazebo built for a woodland garden in Connecticut uses red cedar logs and branches to fit in with the evergreens lining he pathways, while the railings borrow an architectural detail from the house. My process of choosing materials is very much inspired by the work of artist Andy Goldsworthy. He takes nature’s own elements and reworks them into their environment as artwork. I strive to do the same with garden structures without neglecting their functional purpose. The end goal is creating functional works of art that pay homage to the ground that formed them.

Cultivating a Rose Garden

Craig Bergmann

A welcome and recurring daydream I have is walking among an orchard of lanky and luxuriant old shrub roses in their June bloom and heady fragrance. Add a couple of curious Norwich terriers at my feet, and you could be in my garden in Lake Forest, Illinois. The misconceptions of roses—including being too much work or only blooming once—need to be dispelled. There is nothing more lovely in a garden.

Roses have been with us for millennia: men and women have cultivated them since the Bronze Age in Crete, and they grew in the Egypt of the pharaohs. Development of cultivated rose forms was confined for centuries to two distinct geographic regions divided along East-West boundary lines. East included China, Korea, and Japan; the West spanned from the Himalayas to the Atlantic Ocean, including south along the shoreline of North Africa. The earliest Eastern garden rosesappear in apothecary and medicinal gardens before 1400 A.D. in China (Rosa laevigata) andin medieval times in Europe. In the Western world, the earliest mention of a rose wasrecorded in Turkey about 2350 B.C. I think the worldwide heritage of the huge Rosa genus of plants adds to its mystique and status in the garden world. It took aesthetesfrom early European royalty to gentrify this species on most continents and plant it as a hybridization subject. This breeding continues today and has created some amazing examples of what we think a rose is, although probably just as many real experiments that should nothave been let loose in the world.

I have met a number of roses that I haven’t liked, and typically it is those that just provide color without fragrance, foliage color, or fruit for fall interest. Today’s hybrid shrub or landscape roses have become the easy new potentilla or boulder in mall–parking lot plantings. I applaud people gardening anywhere that they can, but dulling down the power of the rose to not even be fragrant seems a horticultural crime. And the brazen color of Knock Out roses is one of the most difficult to blend in the garden—not quite red, not quite pink, just bright. When using Knock Out roses, white and purple seem to be the most contrastable partners.I do design with the modern shrub roses at times, particularly in a mixed perennial garden setting when a more continuous color statement or low-maintenance requirement is in the program, but romance is seldom achieved when used in this way. Some worthy of consideration for a screening or backdrop plant are the Explorer series, including ‘William Baffin’, ‘John Davis’, and ‘John Cabot’, which are some of the largest, hardiest, and showiest of these shrub roses.

I look to roses for inspiration to guide me in transforming a garden into an artfully designed space. A garden should transcend its plan to become a living, dynamic piece of art. It should reference history, place, and the present and be expressive of the maker and its owner. Twenty years ago, I hired a rosarian from Northern California to help my company create a collection of distinctive roses to represent the diversity of the genus and be hardy and thrive in our challenging Midwestern U.S. clime. Gregg Lowery, our rose guru then and now, stressed the true identity of these historic beauties and suggested we propagate these plants from cuttings that would be grown on their own historic, disease-free root structure. What we have learned over the decades of planting own-root roses is that they have more vigor, more disease resistance, and less dieback during our variable cold and often desiccating winters. Today many more roses are available as own-root plants and should be sought out; their use will ensure years of enjoyment in the garden.

Copyrighted images and text used with permission from Rizzoli

ROSE & IVY participates in affiliate link marketing. If you click on a link and purchase something we recommend, we will receive a commission. Thank you for supporting ROSE & IVY!